MicroStevie

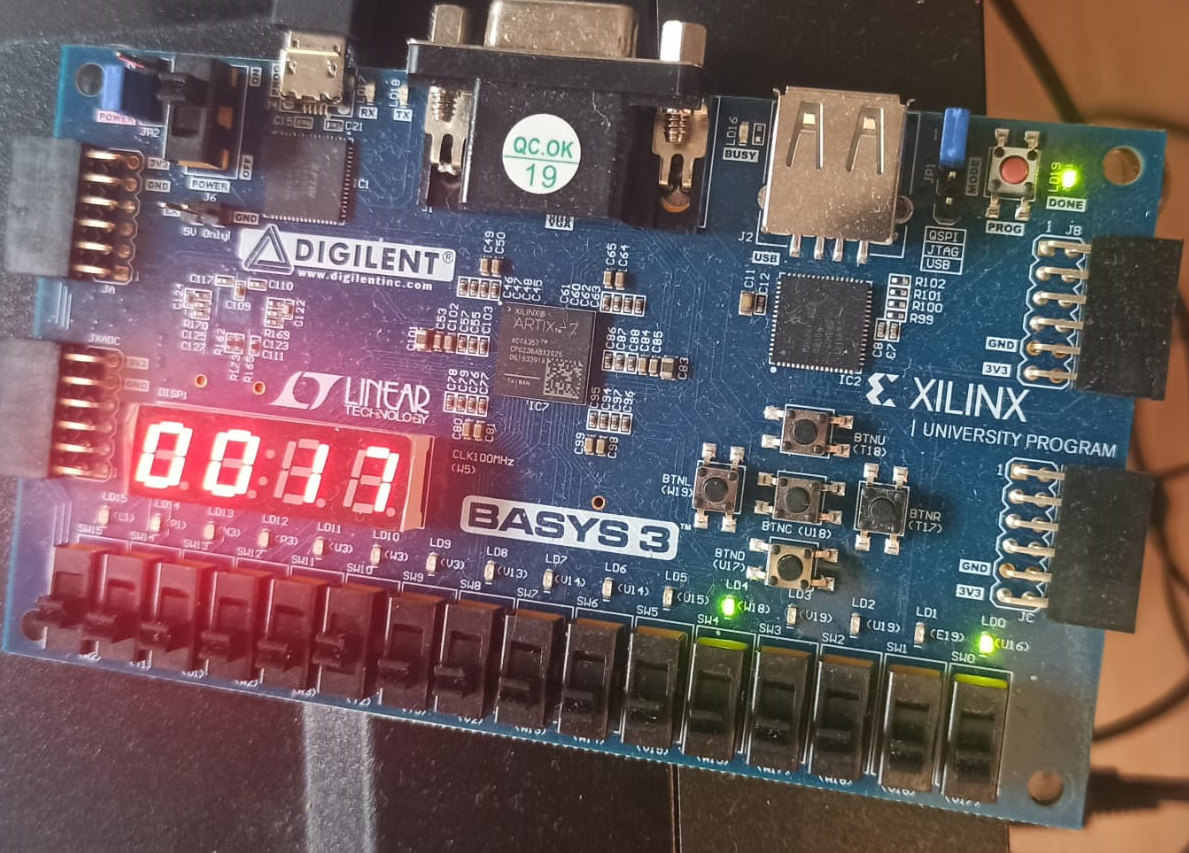

MicroStevie is the implementation of a OISC (= One instruction set computer) CPU using the Basys-3 FPGA and verilog.

How many instructions does a computer need to be turing complete? CISC Architectures like Intel x86 have thousand of different instructions, but what is the bare minimun needed for computation? As is turns out there is only one instruction needed for universal computation. This kind of architectures are called OISC and there are alot of different ways to design this one instruction. In this example I choosed the SUBLEQ instruction.

SUBLEQ => subtract and branch if equal or less

SUBLEQ(A, B, C)

RAM[B] = RAM[B] - RAM[A]

if(RAM[B] <= 0)

goto C

To be fair this instruction is actually combining three instructions, subtract, store in memory and conditional jump. All other OISC instruction are built in a similar way.

With a OISC we save a lot of hardware, since we dont need any decode mechanism, there is only one instruction anyways, so the processor always knows what to execute. The only thing that changes are the parameters.

The OISC architecture is a good (or maybe quite extreme) example of the relationship and interchangeability between hardware and software. Every algorithm can be implemented in hardware directly, or in software using simpler hardware mechanisms (equality of hardware and software). With the OISC architecture we choose to minimize and simplify the hardware to the extreme. There is nothing we can remove from the hardware without making it loose core functionality (turing completness). But this simplicity of the hardware comes with a price, now the sofware is much more complicated. Writing a simple “add” or “multiply” programm requires a lot of thought from the programmer, and many lines of code using just the SUBLEQ instruction. So what we actually did is just to shift the complexity from hardware to software. The art in computer architecture (or in life) is to find a good balance between these two (harware/software, body/mind?).

code: https://github.com/StevenSchuerstedt/MicroStevie

MicroStevie

lets introduce some terminology

address space (total number of addressable entrys of RAM): 2^8, 256

addressability (how many bits in each location): 24

word size (size of one operand the alu can operate on): 24

instructions: 1

Programming FPGA using Verilog

The actual implementation of the CPU uses Verilog and a FPGA. Verilog is a hardware description language (HDL). Unlike programming languages, there is no sequential execution of the code (in a way there is no execution at all..) but only a description what the hardware should look like.

Architecture

The basic architecture follows the von Neumann execution Model, this means data and instructions are in memory and the program is executed sequentially instruction by instruction. (SISD, single instruction / single data, in contrast to SIMD for gpus, parallel processor) The basic components are:

- The MicroStevie CPU, with a address line to controll the ram, and a bus line to output data

- some RAM, with the program and the corresponding data

- a clock, to synchronize everything

The basic computing procedure is very simple, the MicroStevie CPU fetches (loads) the correct instruction from RAM (according to program counter), this instruction is placed in the insruction register and then gets executed. The results are written back into the RAM and the next instruction is fetched.

Control Logic

The control logic is the heart of the cpu. It controls the flow of the modules, so they all can work together.

Fetch Cycle - fetch the next operands from the RAM into the IR

Execution Cycle - execute the SUBLEQ instruction

Registers

Two general purpose registers A and B 24 bits wide, tied directly into the ALU.

A memory address register for the 8 bit address of the RAM.

A instruction register to hold the 24 bit “instruction” (because OISC, only operands), aka three 8 bit operands.

A flags register for the less or equal than 0 flag.

Input/Output

MicroStevie can only output the result of the computation. Input is implicit by programming the ram directly when initializing the fpga. For output I decided for memory-mapped i/o, so only the SUBLEQ instruction is sufficienct for output. I decided memory address 100 is always written to the seven segment display of the fpga.

Future Work

increase speed

There exist several techniques to improve the microarchitecture implementation of an instruction set. Most important today are Pipelining and Superscalar. These techniques increase the throughput of instructions, by using the hardware in a really efficient way. When one instruction is executed the next one will already be fetched at the same time, or multiple instructions are executed at the same time. This requires independence of the instructions, something which is not always guaranteed. So the hardware gets more complicated to handle these cases.

increase functionality

There can be added more hardware to the computer, output hardware like a monitor with vga, or output hardware like keyboards. For a monitor one needs to decide how to interface with the hardware, so there could be some memory cells to address specific pixels on the monitor. For input there has to be some sort of interrupt routine, so the control logic can react to an input event. Currently MicroStevie hast to be programmed by writing directly into the ram, a next step would be to let the system program itself, so use the more advanced input and output mechanis to write a program using MicroStevie and execute it on itself.

This project took roughly ~3 months

some programs

The programs are of the form

mem[X] <= 24’hAABBCC;

Where AA, BB and CC are hex values of the operands for the SUBLEQ instruction.

fibonacci

The fibonacci numbers are calculated in mem[100]

mem[0] <= 24'h110e01;

mem[1] <= 24'h0e1000;

mem[2] <= 24'h0f0f03;

mem[3] <= 24'h646404;

mem[4] <= 24'h100f05;

mem[5] <= 24'h0f6406;

mem[6] <= 24'h0e0e07;

mem[7] <= 24'h100e08;

mem[8] <= 24'h0e1109;

mem[9] <= 24'h0f0f0a;

mem[10] <= 24'h64640b;

mem[11] <= 24'h110f0c;

mem[12] <= 24'h0f640d;

mem[13] <= 24'h0e0e00;

mem[14] <= 0;

mem[15] <= 0;

mem[16] <= 0;

mem[17] <= 1;

primes

The prime numbers are calculated in mem[100]. Including my comments for programming.

mem[0] <= 24'h676707;

mem[1] <= 24'h67670a;

mem[2] <= 24'h68651e; //check if result in 65 is 0 or negative

mem[3] <= 24'h676714; // => number is divisable

mem[4] <= 24'h676704; //hlt

mem[5] <= 24'h6a6406; // => number is not divisable, test next divisor

//increase tested number by 1

mem[20] <= 24'h6b6c15;

mem[21] <= 24'h656516; //clear 65

//mem[21] <= 24'h676716; //clear 65

mem[22] <= 24'h6c6517; //copy number to 65

mem[23] <= 24'h6d6518; //add one

mem[24] <= 24'h6b6b19; //clear

mem[25] <= 24'h6c6c1a;

//reset divisor to two

mem[26] <= 24'h66661b; //clear

mem[27] <= 24'h6e661c; //load 2

mem[28] <= 24'h676700;

//increase divisor by 1

mem[30] <= 24'h6b6c1f;

mem[31] <= 24'h656520; //clear 65

mem[32] <= 24'h6c6521; //copy number to 65

mem[33] <= 24'h6b6b22; //clear

mem[34] <= 24'h6c6c23;

mem[35] <= 24'h686624; //increase divisor by one

mem[36] <= 24'h656c25;

mem[37] <= 24'h6c6b26; //copy number again to 6b

mem[38] <= 24'h6c6c27; //clear 6c

mem[39] <= 24'h666b32; //if branch is taken number is prime

mem[40] <= 24'h6b6b00; //clear 6b and jump back

//number is prime

mem[50] <= 24'h656c33;

mem[51] <= 24'h646434; //clear output

mem[52] <= 24'h6c6435; //output number

mem[53] <= 24'h6c6c36; //clear 6c

mem[54] <= 24'h6d6537; //add one to number

mem[55] <= 24'h666638;

mem[56] <= 24'h6e6639; //reset divisor to two

mem[57] <= 24'h676700; //repeat from begining

//copy number

mem[7] <= 24'h656c08;

mem[8] <= 24'h6c6b09;

mem[9] <= 24'h6c6c0a; //clear 6c

mem[10] <= 24'h666502;

mem[11] <= 24'h676701;

mem[101] <= 2; //number to be tested

mem[102] <= 2; //divisor

mem[103] <= 0; //always 0 to branch

mem[104] <= -1; //always -1 to add one

mem[105] <= -1;

mem[106] <= -2;

mem[107] <= 0; //6b - hold copy of number to test

mem[108] <= 0; //6c

mem[109] <= -1; //6d - add one to number to test

mem[110] <= -2; //always -2 to reset divisor

When dealing with the fpga and programming a CPU I often thought about the reasons and advantages of building a processor first, and then programming the actual problem I would like to solve. For example I could use the fpga (or some basic hardware components) to directly create the fibonacci sequence or the prime numbers, and it would be arguably be less work than to first create a CPU and then programm these things with the CPU. Because what is the CPU actually doing? Well it does nothing on its own and when I want it do to something I need a program and also some input / output mechanisms. When I want it to solve another problem I need to code another program, the same way I would need to build some new hardware. So what is the advantage of building a layer of abstraction first? At first glance it is a lot of more work than to just solve the problem directly. I could build a CPU, then program a Operating System (which also really does nothing on its own), invent a programming language, a compiler etc. just to display the fibonacci numbers, something I could have achieved much simpler by just doing it directly. The power of abstraction is the pushing of limits. When I do everything in hardware directly I am limited by the means the hardware provides me. When I want to solve another problem I might not have the necessary hardware components ready. By using a layer of abstraction (like CPU) these limits almost vanish, the more I move up the ladder. I could still run out of memory if my program requires alot of space, so I would need to get more hardware, but I would argure its more unlikely and there are more things my CPU can do. But there are also limits in the way I solve the problem. With hardware components I am limited to solve my problem in the way the hardware (the physical reality) defines itselve (e.g. logic gates) but when I build a layer of abstraction I can define my own language of solving problems. I can invent a ISA or a programming language, so I can decide how the tools I use for solving my problems should look like. But still I am not completly free in my choices of tools, the logic gates are still kinda present in the sequential progression of a program.